Friday, February 29, 2008

npr on porgy

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4951238

70 Years of Gerswhin's Porgy and Bess

from Day to Day, October 10 2005

by Karen Grigsby Bates

On this day in 1935, Porgy and Bess, George Gershwin's opera about black life in the South Carolina town of Charleston at the turn of the century, made its Broadway debut.

Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, based on DuBose Hayward's successful novel of the same title, tells the story of poor, crippled Porgy and beautiful Bess, who runs away from the fast life to find sanctuary with Porgy and the residents of Catfish Row.

From the very beginning, it was considered another American classic by the composer of "Rhapsody in Blue" — even if critics couldn't quite figure out how to evaluate it. Was it opera, or was it simply an ambitious Broadway musical?

"It crossed the barriers," says theater historian Robert Kimball. "It wasn't a musical work per se, and it wasn't a drama per se — it elicited response from both music and drama critics. But the work has sort of always been outside category."

Borrowing minor chords from his Jewish heritage, call-and-response from black churches he'd visited and dashes of jazz, Gershwin's new music was completely original and very American. It was a commercial failure in its first run on Broadway — but despite that rocky start, Porgy and Bess went on to become one of the most-performed works in theater history.

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

musical notes

- Blog comments to Porgy and Bess posting on listening to Gershwin

- "Exotic Richness of Negro Music and Color of Charleston, S.C., Admirably Conveyed in Score of Catfish Row Tragedy" by Olin Downes (New York Times October 11, 1935)

- "Dramatic Values of Community Legend Gloriouosly Transposed in New Form with Fine Regard for Its Verities" by Brooks Atkinson (New York Times October 11, 1935)

- "Rhapsody in Catfish Row" by George Gershwin (New York Times October 20, 1935)

- "Porgy and Bess--A Folk Opera (a review)" by Hall Johnson (link on blog)

- "The Complicated Life of Porgy and Bess" by James Standifer (link on blog)

- Grove Music Online entry on George Gershwin

- Encyclopedia Britannica Article on George Gershwin

- your JSTOR/MLA/American History secondary source article (and further research perusals)

- List of Musical terms (link on blog, Alice Crawford-Berghof)

- Opera Terms (link on blog)

- Lecture Notes (2/27--see info on gospels/shouts, in particular)

Monday, February 25, 2008

catfish, charleston, and the golden age

DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, from Kendra Hamilton's hypertext version of DuBose's novel, Porgy, which Porgy and Bess was based upon. Novel, critical essay, and pictures of Charleston and Catfish Row: <http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/PORGY/porghome.html>. The first, "haunting" lines of the novel: "Porgy lived in the Golden Age. Not the Golden Age of a remote and legendary past; nor yet the chimerical era treasured by every man past middle life, that never existed except in the heart of youth; but an age when men, not yet old, were boys in an ancient, beautiful city that time had forgotten before it destroyed (11)."

DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, from Kendra Hamilton's hypertext version of DuBose's novel, Porgy, which Porgy and Bess was based upon. Novel, critical essay, and pictures of Charleston and Catfish Row: <http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/PORGY/porghome.html>. The first, "haunting" lines of the novel: "Porgy lived in the Golden Age. Not the Golden Age of a remote and legendary past; nor yet the chimerical era treasured by every man past middle life, that never existed except in the heart of youth; but an age when men, not yet old, were boys in an ancient, beautiful city that time had forgotten before it destroyed (11)."Kendra Hamilton, editor of the hypertext version (follow the above link), writes of Heyward: "Fortunately for the Harlem Renaissance, African-American writers-creating from inside the culture-easily evaded the shoals upon which Van Vechten's kind intentions had foundered. Those who explored "the primitive"--such as Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Jessie Fauset, and Zora Neale Hurston--did so with a generosity of vision undreamed of by the man who considered himself their champion. Such was not the case, however, with the white writers of the period--the Sherwood Andersons, Waldo Franks, Julia Peterkins, and Van Vechtens. Such was not even the case with a writer like Dubose Heyward, whose Porgy was read and admired at least by literary blacks. No less an advocate than Langston Hughes called Heyward one who saw, "with his white eyes, wonderful, poetic qualities in the inhabitants of Catfish Row that makes them come alive . . ."[4]

The Renaissance had long fizzled when Heyward died in 1940, and the nation was engrossed by the spectacle unfolding in Europe-the Nazi advance on Alsace-Lorraine, the fall of the Maginot line, Petain's taking the helm in France. Still Heyward's passing caused the news cycle to pause in its headlong rush for at least a beat. The Charleston papers ran the story next to the lead. Even the national press was lavish in its praise:

"Once the Heywards were among the richest planters of South Carolina . . . It was good fortune for literature and for young Dubose Heyward that the family joined the ranks of the newly poor after the War Between the States," said the New York Times, which also hailed him as the chronicler of the "strange, various, primitive and passionate world"[5] of the Negro.

"[W]ith 'Porgy' Heyward took the first rank," noted the Baltimore Sun. "The humble crippled negro (sic) beggar was a figure made utterly real to Heyward's readers . . . 'Porgy' . . . is, in the most satisfying way, a . . . story written with a skill--no, mastery--that give the reader a sense of fullness, richness, and life."

The New York Tribune, meanwhile, paid the author the highest compliment of all: "His death is a loss for American letters." With these early accounts the elements of Heyward's personal myth seemed firmly in place. The papers stressed a noble ancestry that included a signer of the Declaration of Independence; his family's tragic fall into penury; his personal literary triumphs, earned by dint of hard, lonely effort since his birth couldn't help him and his family was too poor to educate him. Indeed, in the years after Heyward's death, Porgy and Bess, his 1935 collaboration with George Gershwin, was to be revived again and again on Broadway and the West Coast, eventually making a triumphal world tour under the auspices of the State Department from London to Leningrad back through Israel, Egypt, and Central and South America."

Comments on Catfish Row? the Heywards? Dubose Heyward ends the novel with these words: "She looked until she could bear the sight no longer; then she stumbled into her shop and closed the door, leaving Porgy and the goat alone in an irony of morning sunlight." How does this compare with the ending of the opera?

listening to Gershwin

Ella Fitzgerald sings Summertime in Berlin 1968: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NkOuLZ2zcY0>.

Ella Fitzgerald sings Summertime in Berlin 1968: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NkOuLZ2zcY0>.being porgy

Todd Duncan and Anne Brown starred in the original production of Porgy and Bess. poster from original production, 1935. Metropolitan Opera. James Standifer writes, "Gershwin found casting difficult. The Porgy and Bess score required trained voices that could handle operatic content and jazz rhytms and tones. He invited Todd Duncan to his apartment to audition for the role of Porgy. After Duncan sang exactly twelve bars of lungi dal caro bene, Gershwin asked him "Will you be my Porgy?" At a later meeting with Duncan, George and Ira Gershwin went through almost the entire score. Duncan remembers, "I knew it would cause controversy among my people because of its representation of black life and music. But Gershwin had sold me on it right then and there!"

Todd Duncan and Anne Brown starred in the original production of Porgy and Bess. poster from original production, 1935. Metropolitan Opera. James Standifer writes, "Gershwin found casting difficult. The Porgy and Bess score required trained voices that could handle operatic content and jazz rhytms and tones. He invited Todd Duncan to his apartment to audition for the role of Porgy. After Duncan sang exactly twelve bars of lungi dal caro bene, Gershwin asked him "Will you be my Porgy?" At a later meeting with Duncan, George and Ira Gershwin went through almost the entire score. Duncan remembers, "I knew it would cause controversy among my people because of its representation of black life and music. But Gershwin had sold me on it right then and there!"folk operatics

Why did Gershwin call Porgy and Bess a folk opera? What are his various musical influences and how do you see these relating to his notion of this "folk opera"? Where do you or can you hear these various musical influences in the music of Porgy and Bess? What do Atkinson, Downes, or any of the other critics contribute to this discussion of the genre of Porgy and Bess (and why does it matter)? Finally, if Porgy and Bess is a folk opera, what is a folk opera?

Why did Gershwin call Porgy and Bess a folk opera? What are his various musical influences and how do you see these relating to his notion of this "folk opera"? Where do you or can you hear these various musical influences in the music of Porgy and Bess? What do Atkinson, Downes, or any of the other critics contribute to this discussion of the genre of Porgy and Bess (and why does it matter)? Finally, if Porgy and Bess is a folk opera, what is a folk opera?death of the... author

Barthes replaces the concept of the author with the concept of the "scriptor," who is "born simultaneously with the text" (145). Barthes says that because this process is simulateous, the writing is not a "depiction," but is rather a "performative" (145). We talked last week with the film group about how the "performative" nature of Grease was different from the reality of Saving Private Ryan. Does Barthes describe a similar difference? Can we consider Gershwin as a "scriptor"--i.e. someone who deals with a text as a "tissue of quotations (147)," something "drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation (148)"?

Barthes, however, goes further than simply changing the name and function of the author to the scriptor. What does he do? In what sense does the author become the "listener"? What does Barthes mean when he writes, in the very last sentence, that "the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author (148)"?

The Theatre Guild presents Porgy and Bess, music by George Gershwin libretto by DuBose Heyward lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin production directed by Rouben Mamoulian. New York: Gershwin Publishing Corp. [PN G-8-6] [c1935]. [i] (title), pp. 2-7 music, [i] publisher's catalogue of "Songs published separately from the American folk opera Porgy and Bess," including, in addition to the present song, "Bess You Is My Woman," "A Woman Is A Sometime Thing," It Ain't Necessarily So" and "My Man's Gone Now." Copyright in the name of the composer. Inscribed in blue ink to head of title-page: "For Alexander Lindley - With admiration and warm greetings. George Gershwin July 1936 (check day)" [a year to the month before the composer's untimely death at the age of 39]. Very slightly worn and creased; creased at central fold; small edge tears.

"The idea of writing a full-length opera based on DuBose Heyward's novel Porgy, about life among the black inhabitants of 'Catfish Row' in Charleston, South Carolina, first occurred to Gershwin when he read the book in 1926. Heyward's wife Dorothy had later helped him turn Porgy into a successful play, and Heyward had been approached by Al Jolson, who hoped to use the story for a musical show in which he would play the lead in blackface. This plan was rejected, however, and in October 1933 Heyward and the Gershwin brothers signed a contract with the Theatre Guild in New York, the same organization that had produced Porgy on stage. Gershwin began the score in February 1934... During much of the summer of 1934 he stayed in South Carolina, composing and absorbing the local atmosphere... By early 1935 the composition was finished, and Gershwin spent the next several months orchestrating." Richard Crawford in Grove online.

Saturday, February 23, 2008

Assignments: Week Eight

Monday February 25

Reading: view Porgy and Bess

Writing: Final Draft Essay #5 due--upload to http://www.turnitin.com/, make sure to turn in ALL versions/drafts of Essay, including peer emails.

Wednesday February 27

Reading: prompt Essay #5, reviews of Porgy and Bess from Discovery Task

Writing: Discovery Task #4 due, post a comment to one of Porgy and Bess blog questions

Friday February 29

Reading: biographies of George Gershwin from Grove Music Online and Encyclopedia Brittanica; read "Music" chapter and opera and music terms (on blog); sample program notes (Shostakovich, on blog)

Writing: Pre-writing for Essay #6; comment on one more blog post (total: 2, for Porgy and Bess (there are 5 different choices) AND POST A COMMENT/s to the latest post called "musical notes" identifying a/some musical terms.

***Group Music Presentation Today! (please refer to revised chapter on humcore student website)

Friday, February 22, 2008

(social vs. socialst) realism

Socialist Realism, the art produced in accord with the propagandist purposes of the Soviet Communist dictatorship from 1932. It was proclaimed the officially approved artistic idiom in 1934 at the First All-Union Congress, but no clear stylistic guidelines were given. Rather it was defined negatively, in opposition to the ‘formalism’ and ‘intuitivism’ of contemporary movements. These influences were defined as foreign and alien to Marxist theory, particularly during the patriotic aftermath of the Second World War. Typical subjects included large-scale factories, the new collectivist farms, and heroic representations of Stalin as found in The Morning of our Motherland by Fyodor Shurpin (1948; Moscow, Tretyakov Gal.). Such paintings were often on a monumental scale, with easily identifiable figures painted in a superficially naturalistic mode. Idealized depiction was intended to convey to the proletariat the idea that the Soviet dictatorship had succeeded in extinguishing all societal evils. This form of cultural control diminished in Russia after Stalin's death in 1953 but resemblances were later to be found under similar regimes in South-East Asia. (From www.groveart.com, [from OCWA])

and from Encylopedia Brittanica:

Socialist Realism follows the great tradition of 19th-century Russian realism in that it purports to be a faithful and objective mirror of life. It differs from earlier realism, however, in several important respects. The realism of Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov inevitably conveyed a critical picture of the society it portrayed (hence the term critical realism). The primary theme of Socialist Realism is the building of socialism and a classless society. In portraying this struggle, the writer could admit imperfections but was expected to take a positive and optimistic view of socialist society and to keep in mind its larger historical relevance.

A requisite of Socialist Realism is the positive hero who perseveres against all odds or handicaps. Socialist Realism thus looks back to Romanticism in that it encourages a certain heightening and idealizing of heroes and events to mold the consciousness of the masses. Hundreds of positive heroes—usually engineers, inventors, or scientists—created to this specification were strikingly alike in their lack of lifelike credibility. Rarely, when the writer's deeply felt experiences coincided with the official doctrine, the works were successful, as with the Soviet classic Kak zakalyalas stal (1932–34; How the Steel Was Tempered), written by Nikolay Ostrovsky, an invalid who died at 32. His hero, Pavel Korchagin, wounded in the October Revolution, overcomes his health handicap to become a writer who inspires the workers of the Reconstruction. The young novelist's passionate sincerity and autobiographical involvement lends a poignant conviction to Pavel Korchagin that is lacking in most heroes of Socialist Realism.

& Social realism

Term used to refer to the work of painters, printmakers, photographers and film makers who draw attention to the everyday conditions of the working classes and the poor, and who are critical of the social structures that maintain these conditions. In general it should not be confused with Socialist realism, the official art form of the USSR, which was institutionalized by Joseph Stalin in 1934, and later by allied Communist parties worldwide. Social realism, in contrast, represents a democratic tradition of independent socially motivated artists, usually of left-wing or liberal persuasion. Their preoccupation with the conditions of the lower classes was a result of the democratic movements of the 18th and 19th centuries, so social realism in its fullest sense should be seen as an international phenomenon, despite the term’s frequent association with American painting. While the artistic style of social realism varies from nation to nation, it almost always utilizes a form of descriptive or critical realism (e.g. the work in 19th-century Russia of the Wanderers).

Social realism’s origins are traceable to European Realism, including the art of Honoré Daumier, Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. In 19th-century England the Industrial Revolution aroused a concern in many artists for the urban poor. Throughout the 1870s the work of such British artists as Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, Frank Holl (e.g. Seat in a Railway Station—Third Class, wood engraving, 1872) and William Small (e.g. Queue in Paris, wood engraving, 1871) were widely reproduced in The Graphic, influencing van Gogh’s early paintings. Similar concerns were addressed in 20th-century Britain by the Artists international association, Mass observation and the Kitchen sink school. In photography social realism also draws on the documentary traditions of the late 19th century, as in the work of Jacob A. Riis and Maksim Dmitriyev; it reached a culmination in the worker–photographer movements in Europe and the work by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn and others for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) project in the USA in 1935–43 (see Photography, §II).

(from www.groveart.com)

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Sample (Soviet) Citations

Image One: "Workers use old-fashioned brooms to gather grain into a large pile for cleaning." Kazhakstan, circa 1950. Photograph.

Image One: "Workers use old-fashioned brooms to gather grain into a large pile for cleaning." Kazhakstan, circa 1950. Photograph."Workers use old-fashioned brooms to gather grain into a large pile for cleaning." Marxist Internet Archive. "History Archive." Ed. Brian Basgen. 2001. 20 February 2008. <http://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/art/photography/farming/index.htm>.

[headnote (200 words) goes here].

Image Two: Vladimir Malagis. Steel Workers. 1950. Oil on Canvas. 162 cm x 200 cm.

Image Two: Vladimir Malagis. Steel Workers. 1950. Oil on Canvas. 162 cm x 200 cm.Malagis, Vladimir. Steel Workers. The Marxist Internet Archive. "Painting with the Hand and Eye of Marxism" Ed. Brian Bagsen. 2007. 20 February 2008. <http://www.marxists.org/subject/art/visual_arts/painting/index.htm>.

This painting reveals that socialist realism, the official aesthetic of the communist part, is surprisingly not like a photograph. Socialist Realism was founded in part by Maxim Gorky, who began his work as an abstract expressionist (Yedlin 26). In this image, the most prominant feature is the smoke from the steel factory. The workers, immersed and enveloped in this smoke are also somewhat obscured by it. Yet this image, a prototype of socialist realism, offers some insight into what constituted this seemingly straightforward (and yet far too strict) aesthetic sensibility. Since the workers can hardly be seen as individual figures, emphasis is immediately placed upon the imposing environment of the workplace. One of the central efforts of the Soviet regime during the late 40's and early 50's was to deal with the growing disillusionment of the ideal worker and the failure of many communist ideals. Socialist Realism remained as one of the few channels for promoting such values. Without idealizing labor, Malagis manages nonetheless to depict the human strength necessary to overcome such conditions. This combination of the banal and "beautiful" is perhaps one of socialist realism's defining features--the creation of "poetical and at the same time mundane" art ("Soviet Painting" 1).

- single space captions (so that they can fit on one page)

- include alphabetized works cited page at end (for all works used in all 5 images, not separate works cited pages)

- on the introductory page, please include the references to the HCC reader pages. the easiest format for this would be to make a "List of Images," something like the list of illustrations at the beginning of a book, or a table of contexts. It might look like this (this is a sample):

List of Images

Hannah Hoch. "Untitled." Insert above "Beyond the Bauhaus, painters..." HCC Reader, page 41.

Bertolt Brecht. Kuhle Wampe (film still). Insert after "probed for disturbing truths behind the surface appearances of reality." HCC Reader, page 41.

"Kristallnacht." (photograph). Insert above the paragraph which mentions the "Jewish Problem" and "Night of Broken Glass," HCC Reader, page 87.

....and so on...

Friday, February 15, 2008

Pravda Mtsensk Captions

Image One: Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, book cover. Nikolai Leskov.

Image One: Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, book cover. Nikolai Leskov.Opposed to the critical and chaotic air of the opera, this cover image shows a reserved, humanistic perspective of the love strife of Katerina and the unleveled structure of the Russian society. Depicted in this painting, we see a lovestricken Sergey traveling on a path of his past. We see details in the painting such as his black outfit which represents his air of mourning. The tall trees that surround the path he walks in represents the immense growth, wisdom, and experience he has attained. The overall calm and serene setting of the portrait emphasizes the accepted truth of the ways of love and life. In comparing the book and the opera, the book takes a more traditional and comprehensive stance of the tragic love story of Katerina and Sergey. The story was written in 18665, which the opera was written about 69 years later.

On the book cover of the 1994 version of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk, a man in a top hat and a suit is walking on a dirt path in a forest. The original play is by Nikolai Leskov in 1934. Around the time of its original publication, the rise of the National Socialist power was coming into view. The original play was banned in the Soviet Union. The cover shows some bias toward the bourgeiosie because of the man who seems out of place in the cover. The man seems to be walking on a never-ending path.

A little while boy stands on a path in what appears to be the season of autumn. This is a cover for the original short story of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk written in 1895 by Nikolai Leskov. This was made into an opera by Shostakovich, and it reveals the coarsest kind of naturalism. The star of the opera and short story, Katerina, was portrayed as a victim of bourgeios society. On the cover, the white young man is amidst the seasonal change of a dying year as Lady Macbeth or Katerina died due to the overwhelming influence of bourgeious society.

The character on the cover would represent Sergey and the isolation he created for himself. Everyone he’s ever loved has died, because he’s pushed everyone away whether he intended to do that or not. This is possibly due to the fact that he’s moving on while everybody else is left in the past. We see this depicted in the cover as the man is walking towards us which symbolizes him walking away from all his problems as moving on from them. The path that he has traveled has encompassed him because of his past. The cover shows a sense of him being sad, as he is walking away alone, dressed in all black and remembering his past; however, it also shows a direction in the next step in his life of moving forward as he is surrounded by all these bright green trees and receiving a fresh breath of air from them.

Peer Review

Overall Selection:

- comment on the overall variety of their images (correct number of high art, enough difference between images and what each is used to show, correspondence to sections of the Britannica to be illustrated?)

- overall aesthetic/selection criteria for images (the writer may or may not have a separate paragraph at the beginning--either way, you can comment on the type of choice you see being made, if it's clear, too clear, interesting, etc)

For each image:

- Does knowledge of 6 C's seem to be "intimately involved"? In other words, does the author treat the image as a primary source? Again, 6 C's should be implicit in the caption, not explicit, but evidence should be seen that the author has done historical research of the image.

- Is a particular, specific, interesting aspect of the image referred to in the caption? i.e. a concrete detail?

- What idea or a thing does the image represent? Is it convincing that this image should represent the thing or idea?

- Has research been done on the idea or thing that is represented? (again, think of the Hoch/Brugman photo and the research done on "new woman.")

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

cover from film by Peter Weigl, 1992

Please respond in comments to the film or the libretto in the HCC Reader, and you can also consider the Pravda article. Here are some questions to think about:

- Professor Moeller's question is why would Shostakovich think that Lady Macbeth is socialist realism?

- He seems to find that Kusej's film stages "orgasm and murder" as the film's theme, but suggests that he [professor Moeller] would make other choices. How would a different staging communicate a different message?

- PM writes: "Shostakovich intended for Katerina to be a sympathetic character. Do you think she came across as sympathetic in the production video you saw? How would you alter the staging to make her sympathetic?"

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Assignments: Week Seven

Conferences Scheduled; read peer drafts

Wednesday February 13

Reading: see syllabus

Writing: Discovery Task #3, Study Questions (Degenerate Art)

Friday February 15

Reading: Shostakovich Script; "Chaos..." article from Pravda (HCC Reader 134-183)

Writing: Working Draft Essay #5

Forum: 9:00-9:50 and 11:00-11:50 in Crystal Cove (with Professor Moeller and film excerpts from Lady MacBeth)

****office hours Friday changed: 12:00-1:00 in HIB 192

Friday, February 8, 2008

Entartete

Assignments Week Six

for your conference: print out and read (make comments) your peers' drafts. Prepare the drafts to discuss during the conference (refer to Ideas Draft handout/blog). Conferences located at Cyber-A Cafe.

Mandatory viewing: Dmitry Shostakovich, Lady MacBeth of Mtsenk (contact me if none work).

Scheduled showings of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District :

Mon, Feb 11, 2:00-5:00 HH 262 (max cap 82)

Mon, Feb 11, 4:00-7:00 HH 178 (max cap 139)

Tue, Feb 12, 3:00-6:00 HH 254 (max cap 50)

Tue, Feb 12, 7:30-10:20pm HH 254 (max cap 50)

Wed, Feb 13, 2:00-5:00, HSLH 100A (max cap 343)

Thu, Feb 14, 2:00-5:00, HH 108 (max cap 25)

Fri, Feb 15, 2:00-5:00, HSLH 100A (max cap 343)

Also this Week: FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 15: FORUM ON NAZI FILMS WITH PROF. MOELLER IN CRYSTAL COVE AUDITORIUM: 9:00-9:50 AND 11:00-11:50

Monday February 11

Reading: Review HCC Reader 85-133\

Writing: BLog post on "Entartete"

Wednesday February 13

Reading: HCC Reader 134-183 (Lady MacBeth of Mtsenk); Writer's Handbook, Chapter 16 "Analyzing Images"

Writing: Study Questions on Degenerate Art (posted on week six of the syllabus); Discovery Task #3

Also Today: Group "Images" Presentation

Friday February 15

Reading: Writer's Handbook, Chapter 15 "Primary Sources"

Writing: Working Draft due today (please bring 4 copies)

Also Today: Group "Primary Sources" Presentation

Ideas Draft: Essay Five

2. List for the five images as you are considering:

- links to images or titles of images (whatever even minimal form of citation you have, and please note difficulties you are having with citation).

- The passage (with page number) of the HCC Reader that this most closely relates to (it might be several places or a paragraph, so just include where it is most strongly connected.

- Aspects/concepts you are considering focusing on in your headnote (i.e. remember the discussion of the Hoch/Brugman photo which included more info on the “new woman” rather than Hoch as a person or her art or her relationship with Brugman—this is the type of choice you will have to make with your image. In other words, think about what you want the image to represent).

3. For two of your images, include rough drafts of your headnotes/captions. Experiment with the rough draft—it might help you to write more and have your peers and I read it and make suggestions about what is necessary. It might help you to write out the 6 C’s more formally (i.e. to do the chart for each image). Whatever you decide, this part of the process should help you to generate material (i.e. things to say) about the images. If you are not formally using the 6 C’s (content, citation, context, connections, communication, conclusions), remember that they should be “intimately involved” in your headnote writing, but that they should also not simply be listed, and should be included as you see fit in the headnote. Read over the information on Primary Sources, #1 of “5 on Essay Five” Handout, the Writer’s Handbook (112-115), and the information on Professor Moeller’s website on primary sources. This will help you determine what is fit to print.

*******Email this to me and to your peer group by 12 midnight Sunday, February 10. Due to the fact that I will not have easy access to a computer, it is absolutely necessary that I receive the email by the deadline. Please try to cut and paste in the email rather than sending as an attachment. I realize certain typographical details won’t transfer, but I’ll be aware of this. Please print out your peers’ email drafts and spend some time reading them, making helpful comments or questions, before the peer conference on Tuesday and Wednesday.Schedule of conferences (Location: Cyber-A Cafe)--please be considering which time works for you (these will be done in groups of three or four):

Tuesday February 12

11:00-12:00

12:00-1:00

1:00-2:00

2:00-3:00

Wednesday February 13

10:00-11:00

12:00-1:00

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

Claiming the Britannica

Monday, February 4, 2008

The Midterm

These are sample instructions for both parts of the exam--short answer and essay. Following is a list of terms from the first part of the quarter which will be covered on the midterm. Please comment if you have questions.

Short Answer (60%)

Answer SIX out of the following eight questions in 3-5 sentences each. Be sure to respond to each of your six questions directly with specific information from texts, lectures, and class discussions. Your answer must show knowledge of the texts in question. This section of the exam should take you 25-30 minutes. This section is worth 60% of your grade on the midterm.

***one or two of the short answers might also be a passage identification from Shakespeare.

Essay Question (40%)

Answer ONE of the following two questions in a substantial, well-organized essay that takes account of each part of the question. You should offer an introductory paragraph with a thesis claim (which answers all parts of the question). Then offer supporting paragraphs, each with evidence from texts, support, and explanation. In the support section, be sure to provide specific information about the texts you discuss. This section of the exam should take you 20-25 minutes. This section is worth 40% of your grade on the midterm.

Possible themes for the Essay Question: Meanings of the term “making”; Cultural making: weaving of various media, plots & traditions; Role of holidays, celebrations in theater & painting; Various attitudes towards making & the crafts; Art vs. craft; Role of class differences in making of theater & painting; New ambitions for the status of theater & painting; Art and its political context; Art as ideology (reflection or reinforcement of existing political/economic structures); Art as weapon (critique of political/economic structures); Artists to Consider: Botticell (Primavera)i, Hoch (Cut with the Kitchen Knife), Grosz (works from lecture), Kathe Kollwitz (from lecture), Heartfield (Hitler Swallows Money and Spews Nonesense); Photomontage and Film as “new” forms of Art (Hausmann,Heartfield, Grosz, Baader, Brecht)

*****terms below in green are less important.

List of Exam Study Terms

Writer’s Guide

genre

comedy

tragedy

active reading

textual explication

primary vs. secondary sources

Shakespeare

Drama

Comedy vs. tragedy

Reality/Fantasy

Meta-theater

Fancy/Imagination

Forest vs. city

Power and Authority (Athens as Aristotelian City)

Socioeconomic Class

Relationship of crafts (rude mechanicals) to theatrical making

Shakespeare as a “maker”

Shakespeare as a weaver of traditions

Classical myths in MSND

English folklore & holidays in MSND

Function of magic in MSND

Function of holidays for real communities and for MSND

Metamorphosis

Shakespeare’s several audiences

Shakespeare’s ambitions for new theater (poetic art plus craft)

Arguments about marriage & its significance in MSND

Political significance of marriage

Coercion, consent, accommodation

apprehension / comprehension (Theseus’ speech on the imagination)

constancy (Hippolyta’s reply)

wall, chink, moonshine (their significance as metaphors)

Gains & losses for the characters at the end of MSND

Naming, as a form of Making

Alberti

Renaissance humanism

Alberti’s ambitions for painting as an art

Liberal arts (esp. geometry and rhetoric)

Alberti’s use of Aristotle’s rhetoric

Logos (istoria)

Ethos (in painting); dignity; appropriateness

Pathos (in painting)

Formal aspects of painting: line, composition, color

Commentator figure

Various audiences for painting (according to Alberti)

Painters’ education

Botticelli

La Primavera (1482) [link available on our section website under “Paintings” tab]

Botticelli’s connection to the crafts

Occasion for the production of La Primavera

Intended placement & function of La Primavera

Istoria of La Primavera

Ethos & pathos of figures

Chloris & Zephyr

Flora

metamorphosis

Calendimaggio

Three Graces: Chastity, Desire, Beauty

Liberality

Venus (compare Venus from The Birth of Venus)

Cupid

Mercury

Types of love depicted in La Primavera

Art in Weimar/Nazi Germany

Methods of the historian

Context

Making & doing together (“Can a maker ever NOT be a doer?”)

6 C’s of Historical Understanding

Relationship of art and politics (“Can art be political? Can artists help make a revolution?”)

Karl Marx

Relationship of art and economics

Capitalism

Communism

Socialism

Bourgeoisie

Proletariat

Ideology

Labor expropriation (surplus value)

World War I

Treaty of Versailles

War Guilt / war debt

Russian (Bolshevik) Revolution

Lenin

Weimar Republic

Majority Socialists (Ebert)

Spartacus League (Liebknecht, Luxemburg)

Dadaism

Dada Manifesto

Expressionism

Dadaists’ complaints against “art”

“Art Scabs”

Bauhaus

Gropius

Grosz: political arguments in his art (see images on Moeller’s site)

Heartfield: political arguments in his art (see images)

Photomontage & its political significance

Hoch: political & gender arguments in her art (see images)

“The new woman”: androgyny, same-sex relationships

Aesthetic

Brecht, Realism

Function of Art: Communication, Expression, Document

Study Question Link: https://eee.uci.edu/08w/29011/home/Questions+from+Britannica.doc

Friday, February 1, 2008

Assignments: Week Five

Reading: see Syllabus

Writing: post comment on each of sample captions (Hoch and Schwitters) by 9 pm Sunday night & post response on the brecht blog post, "Who owns the world?"; Begin document searching--email me to ask questions about essay and images.

**turn in Study Questions (optional)

Wednesday February 6

Reading: see Syllabus, Midterm Review Sheet

Writing: study study study

Friday February 8

Midterm Exam (in Discussion Section)

who owns the world?

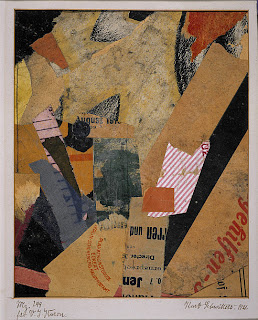

Sample Caption II: Schwitters

Comment on the above caption. What would you add or take out? What type of information is focused on in the sample? What would you do differently?

Sample Caption I: Hoch

Höch and Til Brugman, her partner from 1926 to 1935

Höch and Til Brugman, her partner from 1926 to 1935Photograph: Black & White

http://www.humanities.uci.edu/~rmoeller/HCC_Lectures/RGM_Lecture2.html

In the 1920s, the Weimar Republic, named for the town in central Germany where a new German constitution was drafted in 1919, became known throughout Europe for its encouragement of all sorts of experimentation—musical, artistic, even sexual. Although a global phenomenon, the “new woman,” characterized by her short hair cut, her androgynous dress, and her independence seemed to be particularly at home in the Weimar Republic. Particularly, in big cities like Berlin, Weimar opened up a space in which it was possible for women to enjoy same-sex relations with women in public spaces. In her 1929 book, Else Hermann described What the New Woman Is Like. Although this vision of the “new woman” was well beyond the reach of many urban working-class women and posed a threat to more traditional women of all classes, Hermann suggests some of the ways in which conceptions of appropriate femininity were subject to redefinition in the Weimar years. One such, “new woman” was Hannah Höch, a part of the Berlin Dadaist movement. In the 1920s in Germany, explicitly political art was almost exclusively produced by men and offered depictions of women that clearly reflected a male perspective. Women typically appeared as the downtrodden victims of the capitalist system, forced into poverty and unwanted pregnancy, or as prostitutes, slaves in a different way to the capitalist system. Höch was exceptional not only because she was a woman in an artistic world dominated by men, but also because she offered a much more nuanced commentary on the status of women in the Weimar Republic. (words: 258)

Reprinted in Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg, eds., The Weimar Sourcebook (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 206-7.

Comment on the above caption. What would you add or take out? What type of information is focused on in the sample? What would you do differently?